Parallel raster computations using Dask

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I parallelize computations on rasters with Dask?

How can I determine if parallelization improves calculation speed?

What are good practices in applying parallelization to my raster calculations?

Objectives

Profile the timing of the raster calculations.

Open raster data as a chunked array.

Recognize good practices in selecting proper chunk sizes.

Setup raster calculations that take advantage of parallelization.

Introduction

Very often raster computations involve applying the same operation to different pieces of data. Think, for instance, to the “pixel”-wise sum of two raster datasets, where the same sum operation is applied to all the matching grid-cells of the two rasters. This class of tasks can benefit from chunking the input raster(s) into smaller pieces: operations on different pieces can be run in parallel using multiple computing units (e.g., multi-core CPUs), thus potentially speeding up calculations. In addition, working on chunked data can lead to smaller memory footprints, since one may bypass the need to store the full dataset in memory by processing it chunk by chunk.

In this episode, we will introduce the use of Dask in the context of raster calculations. Dask is a Python library for

parallel and distributed computing. It provides a framework to work with different data structures, including chunked

arrays (Dask Arrays). Dask is well integrated with (rio)xarray objects, which can use Dask arrays as underlying

data structures.

Dask

This episode shows how Dask can be used to parallelize operations on local CPUs. However, the same library can be configured to run tasks on large compute clusters.

More resources on Dask:

- Dask and Dask Array.

- Xarray with Dask.

It is important to realize, however, that many details determine the extent to which using Dask’s chunked arrays instead of regular Numpy arrays leads to faster calculations (and lower memory requirements). The actual operations to carry out, the size of the dataset, and parameters such as the chunks’ shape and size, all affects the performance of our computations. Depending on the specifics of the calculations, serial calculations might actually turn out to be faster! Being able to profile the computational time is thus essential, and we will see how to do that in a Jupyter environment in the next section.

Time profiling in Jupyter

Introduce the Data

We’ll continue from the results of the satellite image search that we have carried out in an exercise from a previous episode. We will load data starting from the

search.jsonfile.If you would like to work with the data for this lesson without downloading data on-the-fly, you can download the raster data using this link. Save the

geospatial-python-raster-dataset.tar.gzfile in your current working directory, and extract the archive file by double-clicking on it or by running the following command in your terminaltar -zxvf geospatial-python-raster-dataset.tar.gz. Use the filegeospatial-python-raster-dataset/search.json(instead ofsearch.json) to get started with this lesson.

Let’s set up a raster calculation using assets from our previous search of satellite scenes. We first load the item

collection using the pystac library:

import pystac

items = pystac.ItemCollection.from_file("search.json")

We select the last scene, and extract the URLs of two assets: the true-color image (“visual”) and the scene classification layer (“SCL”). The latter is a mask where each grid cell is assigned a label that represents a specific class e.g. “4” for vegetation, “6” for water, etc. (all classes and labels are reported in the Sentinel-2 documentation, see Figure 3):

assets = items[-1].assets # last item's assets

visual_href = assets["visual"].href # true color image

scl_href = assets["SCL"].href # scene classification layer

Opening the two assets with rioxarray shows that the true-color image is available as a raster file with 10 m

resolution, while the scene classification layer has a lower resolution (20 m):

import rioxarray

scl = rioxarray.open_rasterio(scl_href)

visual = rioxarray.open_rasterio(visual_href)

print(scl.rio.resolution(), visual.rio.resolution())

(20.0, -20.0), (10.0, -10.0)

In order to match the image and the mask pixels, we take advantage of a feature of the cloud-optimized GeoTIFF (COG) format, which is used to store these raster files. COGs typically include multiple lower-resolution versions of the original image, called “overviews”, in the same file. This allows to avoid downloading high-resolution images when only quick previews are required.

Overviews are often computed using powers of 2 as down-sampling (or zoom) factors (e.g. 2, 4, 8, 16). For the true-color image we thus open the first level overview (zoom factor 2) and check that the resolution is now also 20 m:

visual = rioxarray.open_rasterio(visual_href, overview_level=0)

print(visual.rio.resolution())

(20.0, -20.0)

We can now time profile the first step of our raster calculation: the (down)loading of the rasters’ content. We do it by

using the Jupyter magic %%time, which returns the time required to run the content of a cell:

%%time

scl = scl.load()

visual = visual.load()

CPU times: user 729 ms, sys: 852 ms, total: 1.58 s

Wall time: 40.5 s

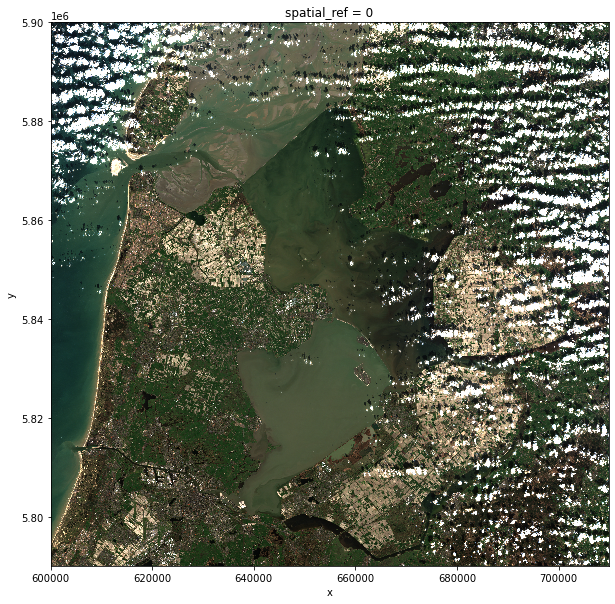

visual.plot.imshow(figsize=(10,10))

scl.squeeze().plot.imshow(levels=range(13), figsize=(12,10))

After loading the raster files into memory, we run the following steps:

- We create a mask of the grid cells that are labeled as “cloud” in the scene classification layer (values “8” and “9”, standing for medium- and high-cloud probability, respectively).

- We use this mask to set the corresponding grid cells in the true-color image to null values.

- We save the masked image to disk as in COG format.

Again, we measure the cell execution time using %%time:

%%time

mask = scl.squeeze().isin([8, 9])

visual_masked = visual.where(~mask, other=visual.rio.nodata)

visual_masked.rio.to_raster("band_masked.tif")

CPU times: user 270 ms, sys: 366 ms, total: 636 ms

Wall time: 647 ms

We can inspect the masked image as:

visual_masked.plot.imshow(figsize=(10, 10))

In the following section we will see how to parallelize these raster calculations, and we will compare timings to the serial calculations that we have just run.

Dask-powered rasters

Chunked arrays

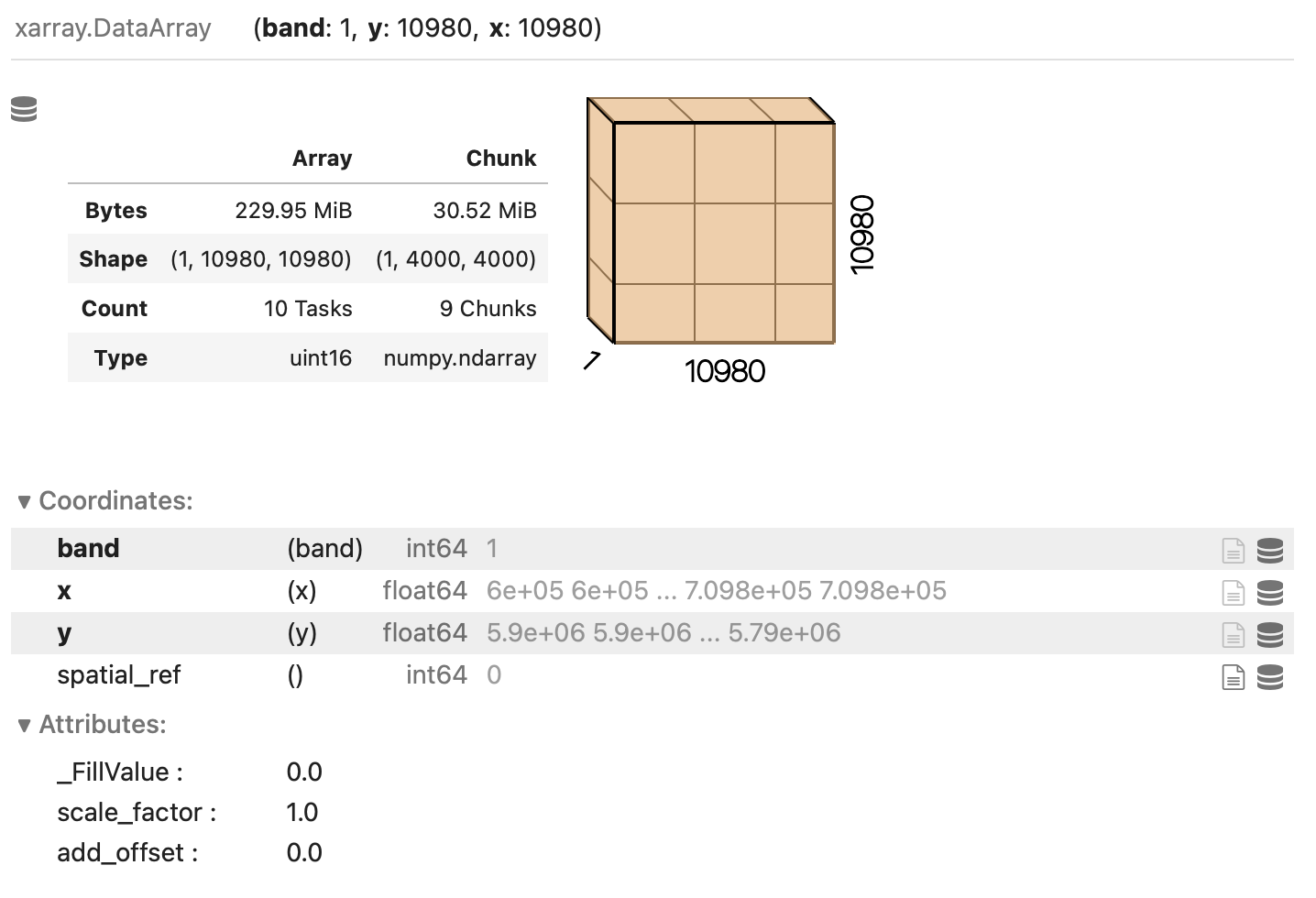

As we have mentioned, rioxarray supports the use of Dask’s chunked arrays as underlying data structure. When opening

a raster file with open_rasterio and providing the chunks argument, Dask arrays are employed instead of regular

Numpy arrays. chunks describes the shape of the blocks which the data will be split in. As an example, we

open the blue band raster (“B02”) using a chunk shape of (1, 4000, 4000) (block size of 1 in the first dimension and

of 4000 in the second and third dimensions):

blue_band_href = assets["B02"].href

blue_band = rioxarray.open_rasterio(blue_band_href, chunks=(1, 4000, 4000))

Xarray and Dask also provide a graphical representation of the raster data array and of its blocked structure.

Exercise: Chunk sizes matter

We have already seen how COGs are regular GeoTIFF files with a special internal structure. Another feature of COGs is that data is organized in “blocks” that can be accessed remotely via independent HTTP requests, enabling partial file readings. This is useful if you want to access only a portion of your raster file, but it also allows for efficient parallel reading. You can check the blocksize employed in a COG file with the following code snippet:

import rasterio with rasterio.open(visual_href) as r: if r.is_tiled: print(f"Chunk size: {r.block_shapes}")In order to optimally access COGs it is best to align the blocksize of the file with the chunks employed when loading the file. Open the blue-band asset (“B02”) of a Sentinel-2 scene as a chunked

DataArrayobject using a suitable chunk size. Which elements do you think should be considered when choosing the chunk size?Solution

import rasterio with rasterio.open(blue_band_href) as r: if r.is_tiled: print(f"Chunk size: {r.block_shapes}")Chunk size: [(1024, 1024)]Ideal chunk size values for this raster are thus multiples of 1024. An element to consider is the number of resulting chunks and their size. Chunks should not be too big nor too small (i.e. too many). As a rule of thumb, chunk sizes of 100 MB typically work well with Dask (see, e.g., this blog post). Also, the shape might be relevant, depending on the application! Here, we might select a chunks shape of

(1, 6144, 6144):band = rioxarray.open_rasterio(blue_band_href, chunks=(1, 6144, 6144))which leads to chunks 72 MB large: ((1 x 6144 x 6144) x 2 bytes / 2^20 = 72 MB). Also, we can let

rioxarrayand Dask figure out appropriate chunk shapes by settingchunks="auto":band = rioxarray.open_rasterio(blue_band_href, chunks="auto")which leads to

(1, 8192, 8192)chunks (128 MB).

Parallel computations

Operations performed on a DataArray that has been opened as a chunked Dask array are executed using Dask. Dask

coordinates how the operations should be executed on the individual chunks of data, and runs these tasks in parallel as

much as possible.

Let’s now repeat the raster calculations that we have carried out in the previous section, but running calculations in parallel over a multi-core CPU. We first open the relevant rasters as chunked arrays:

scl = rioxarray.open_rasterio(scl_href, lock=False, chunks=(1, 2048, 2048))

visual = rioxarray.open_rasterio(visual_href, overview_level=0, lock=False, chunks=(3, 2048, 2048))

Setting lock=False tells rioxarray that the individual data chunks can be loaded simultaneously from the source by

the Dask workers.

As the next step, we trigger the download of the data using the .persist() method, see below. This makes sure that the downloaded

chunks are stored in the form of a chunked Dask array (calling .load() would instead merge the chunks in a single

Numpy array).

We explicitly tell Dask to parallelize the required workload over 4 threads. Don’t forget to add the Jupyter magic to record the timing!

%%time

scl = scl.persist(scheduler="threads", num_workers=4)

visual = visual.persist(scheduler="threads", num_workers=4)

CPU times: user 1.18 s, sys: 806 ms, total: 1.99 s

Wall time: 12.6 s

So downloading chunks of data using 4 workers gave a speed-up of almost 4 times (40.5 s vs 12.6 s)!

Let’s now continue to the second step of the calculation. Note how the same syntax as for its serial version is employed for creating and applying the cloud mask. Only the raster saving includes additional arguments:

tiled=True: write raster as a chunked GeoTIFF.lock=threading.Lock(): the threads which are splitting the workload must “synchronise” when writing to the same file (they might otherwise overwrite each other’s output).compute=False: do not immediately run the calculation, more on this later.

from threading import Lock

%%time

mask = scl.squeeze().isin([8, 9])

visual_masked = visual.where(~mask, other=0)

visual_store = visual_masked.rio.to_raster("band_masked.tif", tiled=True, lock=Lock(), compute=False)

CPU times: user 13.3 ms, sys: 4.98 ms, total: 18.3 ms

Wall time: 17.8 ms

Did we just observe a 36x speed-up when comparing to the serial calculation (647 ms vs 17.8 ms)? Actually, no calculation has run yet. This is because operations performed on Dask arrays are executed “lazily”, i.e. they are not immediately run.

Dask graph

The sequence of operations to carry out is stored in a task graph, which can be visualized with:

import dask dask.visualize(visual_store)

The task graph gives Dask the complete “overview” of the calculation, thus enabling a better management of tasks and resources when dispatching calculations to be run in parallel.

While most methods of DataArray’s run operations lazily when Dask arrays are employed, some methods by default

trigger immediate calculations, like the method to_raster() (we have changed this behaviour by specifying

compute=False). In order to trigger calculations, we can use the .compute() method. Again, we explicitly tell Dask

to run tasks on 4 threads. Let’s time the cell execution:

%%time

visual_store.compute(scheduler="threads", num_workers=4)

CPU times: user 532 ms, sys: 488 ms, total: 1.02 s

Wall time: 791 ms

The timing that we have recorded for this step is now closer to the one recorded for the serial calculation (the parallel calculation actually took slightly longer). The explanation for this behaviour lies in the overhead that Dask introduces to manage the tasks in the Dask graph. This overhead, which is typically of the order of milliseconds per task, can be larger than the parallelization gain, and this is typically the case for calculations with small chunks (note that here we have used chunks that are only 4 to 32 MB large).

Key Points

The

%%timeJupyter magic command can be used to profile calculations.Data ‘chunks’ are the unit of parallelization in raster calculations.

(

rio)xarraycan open raster files as chunked arrays.The chunk shape and size can significantly affect the calculation performance.

Cloud-optimized GeoTIFFs have an internal structure that enables performant parallel read.