To understand a picture, it helps to know how it was made. So before we start looking at the structures of cells, let us quickly cover some of the techniques we use to see them.

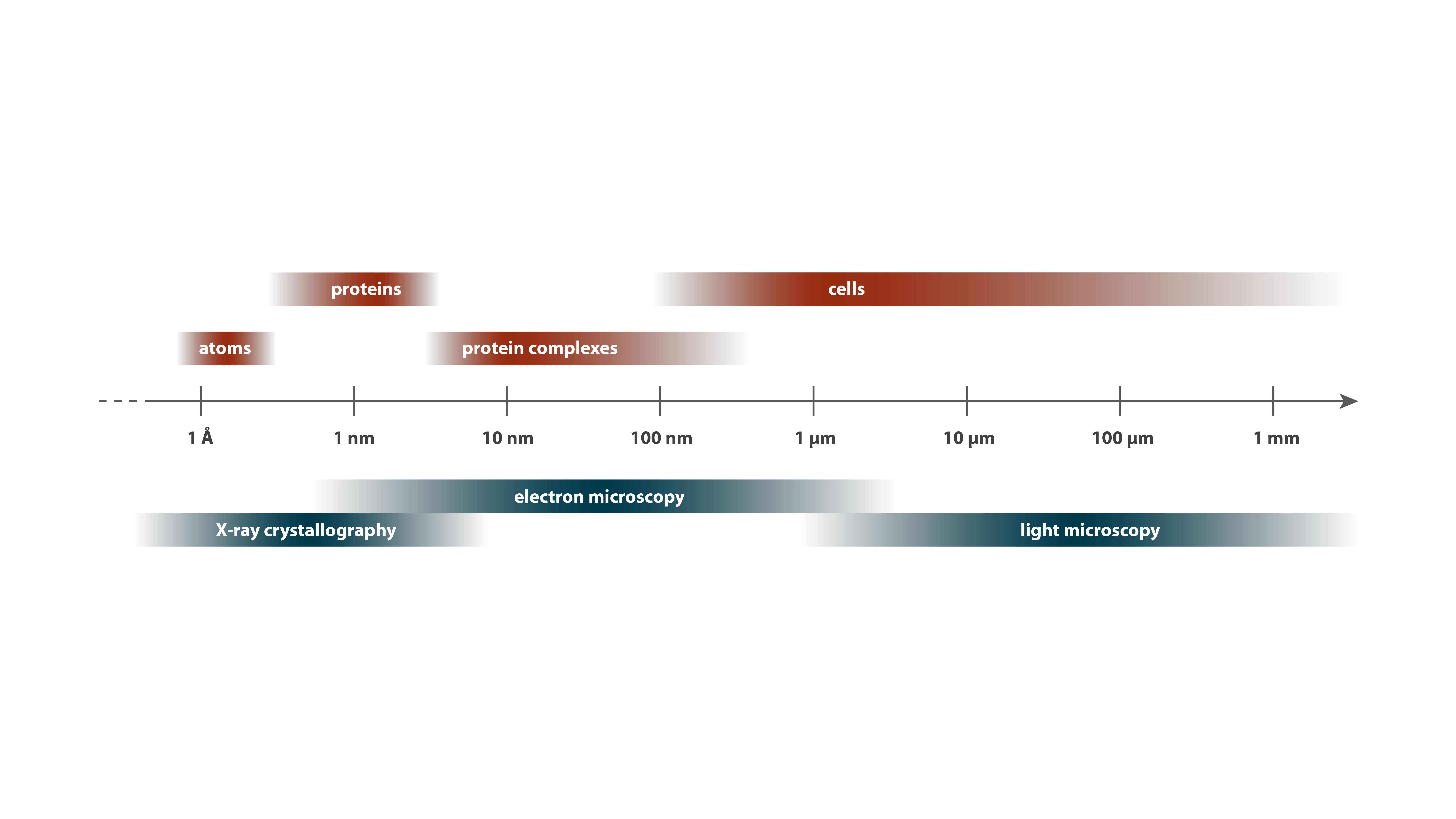

Cell biology occurs over a vast scale, from angstrom-level (0.1 nm) rearrangements of molecules inside cells to millimeter-level (1,000,000 nm) interactions between cells. Different tools of structural biology cover different ranges of this scale, complementing one another to provide a more complete view (Learn More below ⇩). To discuss these tools, we will start at the “big” end of the scale and work our way down, from light microscopy to electron microscopy to X-ray crystallography. Our guide will be a cellular structure called the flagellum, which bacteria use to swim (you will see how it works in Chapter 6).

Bacteria and archaea are, with very few exceptions, invisible to our eyes. As you can see with these Staphylococcus aureus being chased through a field of human blood cells by an immune cell, they are orders of magnitude smaller even than eukaryotic cells. As a consequence, they were unknown to us until about 350 years ago, in the seventeenth century, when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek created the first microscopes capable of revealing such tiny cells. The simplest microscope is a magnifying glass which, combined with the lens of your eye, produces a magnified image on your retina. A compound microscope has two or more lenses, whose magnifications multiply, and this is what we commonly mean when we refer to a “light microscope.”

The cells here were imaged by light microscopy, captured on film by David Rogers in the 1950s [7]. They illustrate how light microscopy can reveal general properties, such as the shape, of cells. The video also illustrates how light microscopy can capture not just single snapshots of cells, but how they grow, divide and move over time.