How else might your cell deal with the crowd? Well, if you can’t join them, maybe you should try to beat (and eat) them. Bacteria have evolved an impressive arsenal of molecular weaponry. In fact, most of the antibiotics we use were invented by bacteria. In many cases, cells simply release these antibiotics to the environment, either directly or in membrane vesicles, which may travel further. For more specific targeting, though, cells employ a varied array of secretion systems. You already saw some of these nanomachines in Chapter 6: a type III secretion system assembles the flagellum and a type II secretion system assembles the archaellum. Another type II secretion system makes (and unmakes) type IV pili. Other family members have evolved more militaristic functions.

Type II secretion systems (T2SSs) in Legionella pneumophila like this pump out effector proteins that enable a complex pathogenic lifecycle. L. pneumophila live in several environments: inside amoebae, outside cells (but sometimes with others in biofilms), and inside our cells, where they cause the severe pneumonia known as Legionnaires’ disease. In each environment, the T2SS pumps out proteins that facilitate growth there. For instance, once we inhale L. pneumophila with water droplets, they are internalized by our macrophages. They then use their T2SSs to secrete proteins that prevent their pockets in the cell (called Legionella-containing vacuoles) from being degraded, and suppress our innate immune response. This gives the bacteria time to replicate and establish a persistent colony. The T2SSs also secrete a toxin protein that breaks down lung tissue.

Unlike the secretion systems in Chapter 6, the T2SS does not build an extracellular appendage. Instead, it is thought to work by pumping proteins through the envelope channel using a short piston-like “pseudo-pilus” (⇩), pushing the molecules into the extracellular space. (Keep in mind that for these intracellular pathogens, their extracellular space is the interior of the host cell.)

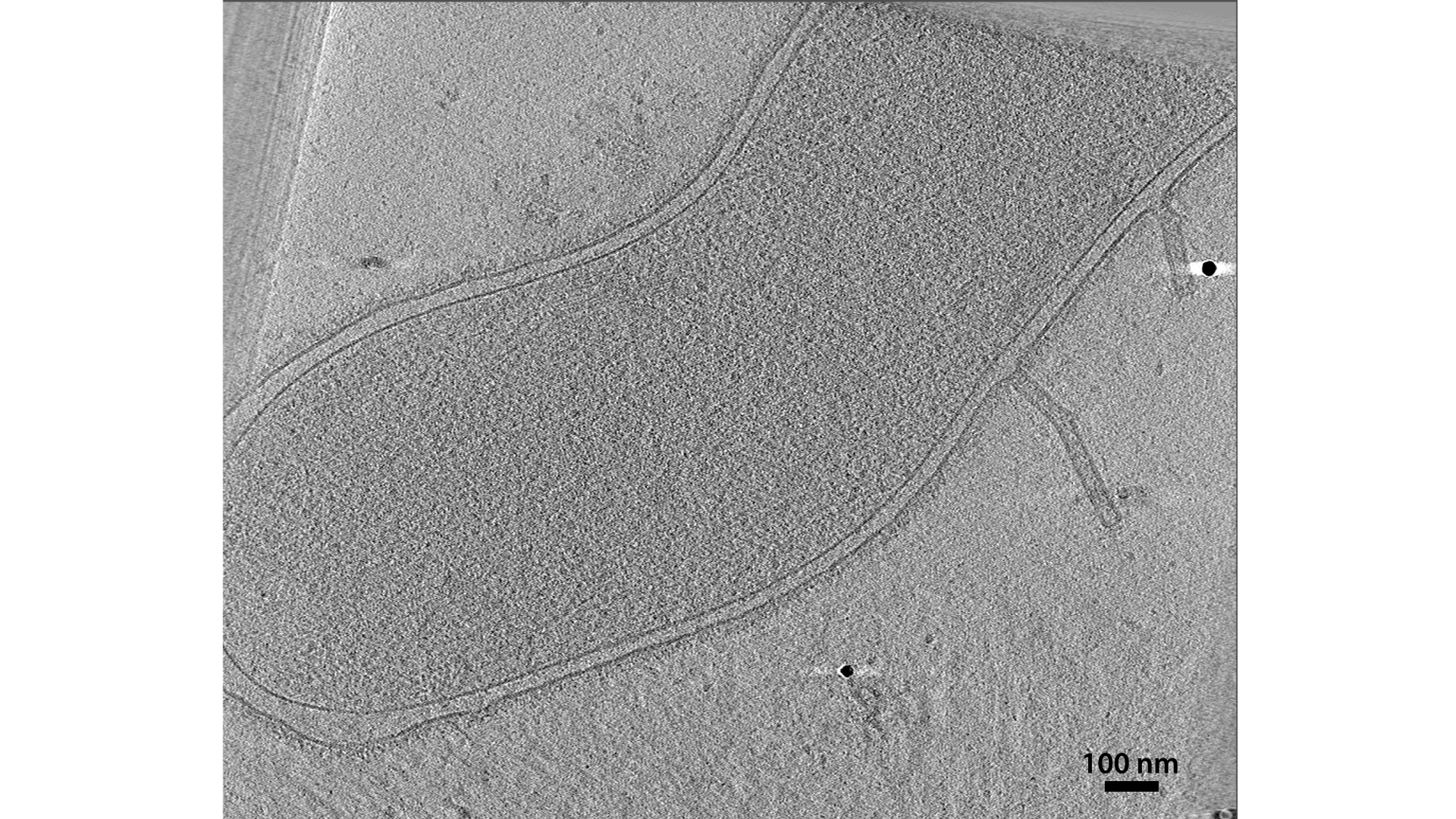

L. pneumophila also use another, unrelated machine, a type IV secretion system (T4SS), to deliver more than 400(!) different kinds of effector proteins into host cells to promote infection. You can see multiple inactive T4SSs in this cell (⇩). We do not yet know what they look like during active secretion, so the mechanism remains unclear. In another human pathogen, Helicobacter pylori, inactive T4SSs are sometimes seen next to mysterious extracellular tubes, raising the intriguing possibility that the structures are somehow related (⇩).

This L. pneumophila cell is not unusual; it is common for pathogenic bacteria to employ multiple types of secretion systems. The bristling arsenal of bacteria is a fearsome thing.