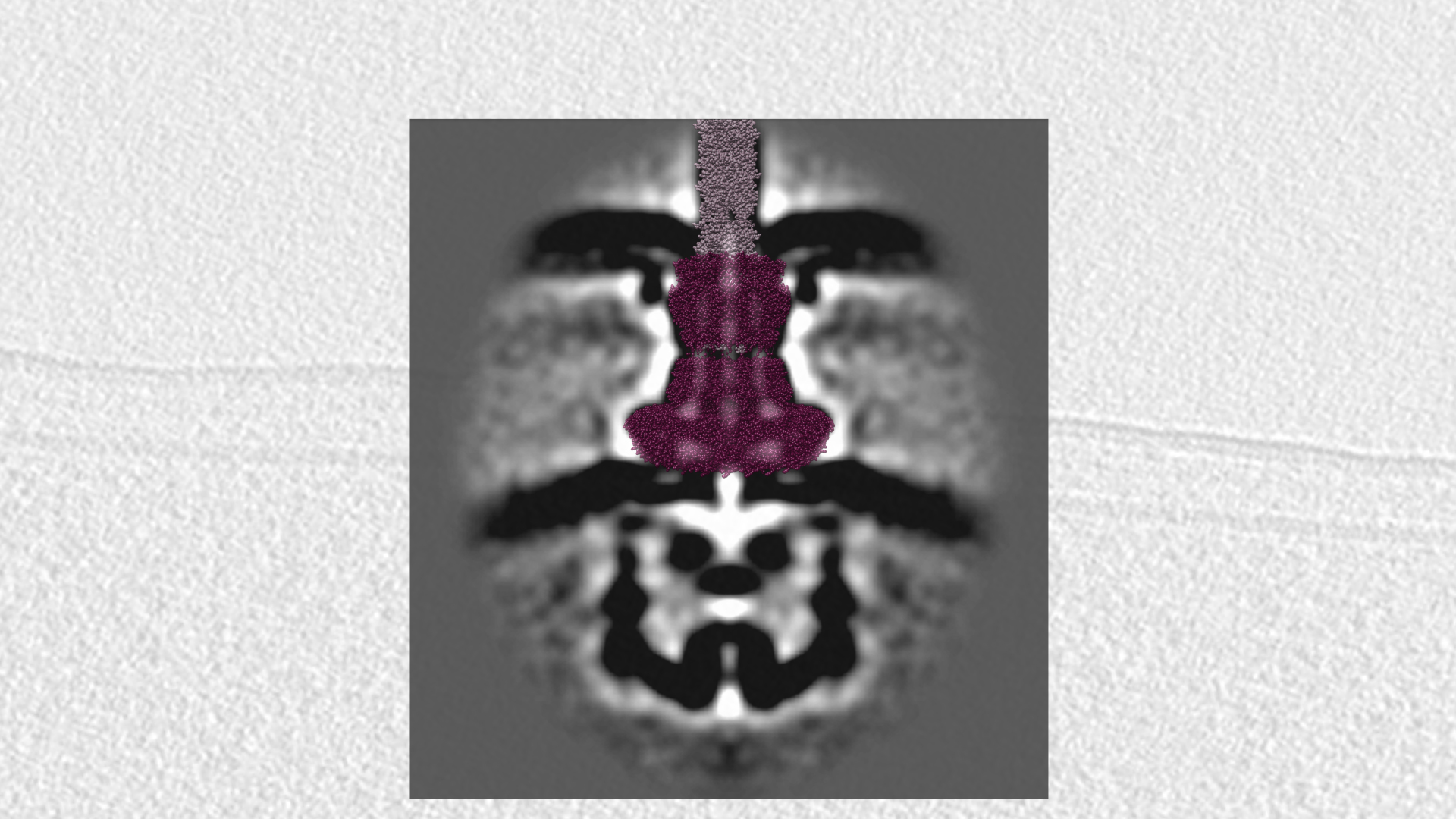

What if your cell wanted to go a step further and deliver toxins directly into its target? Perhaps it needs a syringe. One of the most common, and best-studied, pathogenic secretion systems is the type III secretion system (T3SS) that assembles a needle-like toxin delivery system called the injectisome. T3SS injectisomes and flagellar motors are closely related, and the basal machines have similar structures (⇩). Rather than assembling a long helical filament for motility, though, injectisomes form a shorter needle, which you can see on this Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The needle can penetrate a eukaryotic cell, delivering effectors directly into its cytoplasm that block the immune response of the host, and lead to cell lysis. (You can watch an animation of this process on YouTube.)

Note: It would be wasteful, or detrimental, for your cell to secrete toxins all the time. Pathogens typically have multi-stage lifecycles, often passing through an intermediate host and/or the environment. Pathogenic machinery like secretion systems are typically only produced when conditions signal that the cell has reached its target (e.g. increased temperature or salt concentration). Until then, the genes encoding the protein components are turned off. This cell is missing a protein (ExsD) that turns off expression of these injectisome components. As a result, the strain makes injectisomes even outside the host, enabling us to image their structure.

T3SSs are closely related to type II secretion systems (T2SSs) and share a common element: the channel embedded in the outer membrane, formed by many copies of a protein called a Secretin (⇩). The rest of the machine looks very different, though, reflecting their evolution into separate mechanisms.