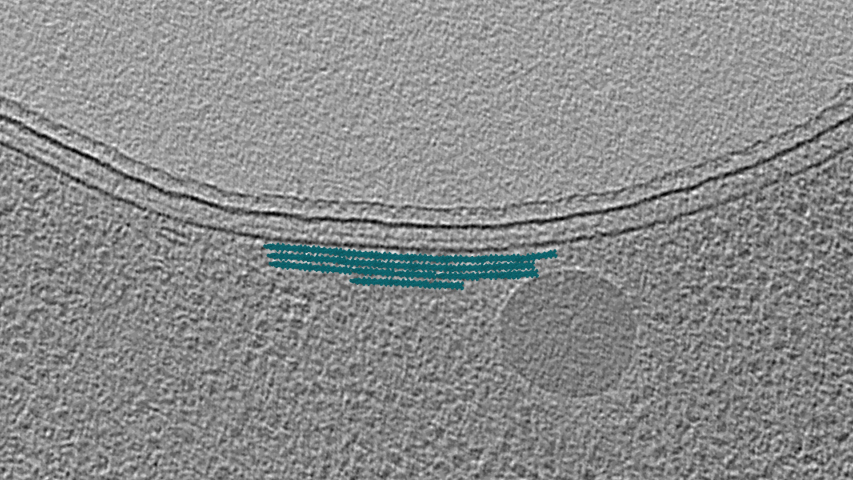

CTP synthase is a ubiquitous metabolic protein found throughout all domains of life that helps make the building blocks of RNA and DNA. It also polymerizes into filaments. In eukaryotes, the filament structure activates the enzyme. In bacteria, the filament structure (shown here for Escherichia coli [31]) inhibits the enzyme’s metabolic function. Polymerization of enzymes is fairly common, providing an elegant way to quickly regulate the activity of a protein that may not always be needed, but would be costly or slow to degrade and synthesize again. You will see another example in Chapter 4. In the case of CTP synthase, the cytoskeletal role likely arose secondarily; once you have a long filament lying around, why not use it as a scaffold?