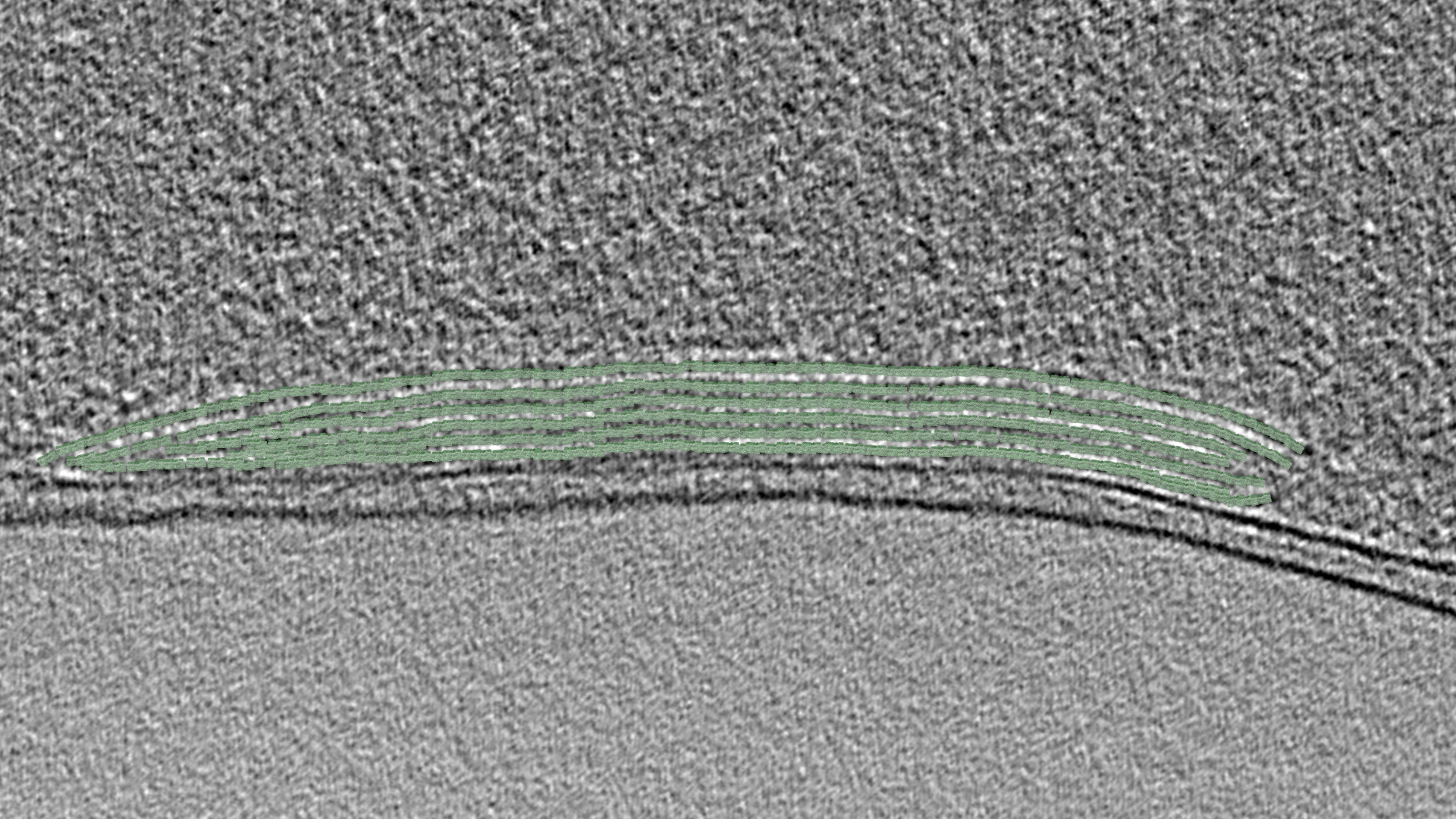

Photosynthetic bacteria harvest energy from sunlight using protein complexes (⇩) embedded in their membrane. An easy way to increase the light-gathering capability of such a cell would be to expand the membrane, but then the cell’s volume would also increase. To get around this problem, why not stack the extra membrane inside the cell? Many (but not all) photosynthetic bacteria contain intracytoplasmic membrane, or ICM. In cells like this Rhodopseudomonas palustris, the ICM is continuous with the inner membrane, forming stacks at the middle of the cell. These stacks grow and shrink as needed, depending on light conditions and the cell’s metabolic state. Different species have different, and more extensive, arrangements (⇩). ICM may remind you of the thylakoid membranes of eukaryotic chloroplasts, and for good reason; chloroplasts evolved from photosynthetic bacteria that likely lived symbiotically inside a eukaryotic precursor of modern plants.

Other photosynthetic bacteria have taken the specialization of their light-harvesting membranes a step further, expanding not the entire membrane, but simply the hydrophobic interior. The result is a sort of factory called a chlorosome with hundreds of thousands of photocomplexes packed tightly inside a lipid monolayer. Chlorosomes, and other compartments you will see soon, challenge the idea that organelles exist only in eukaryotes.