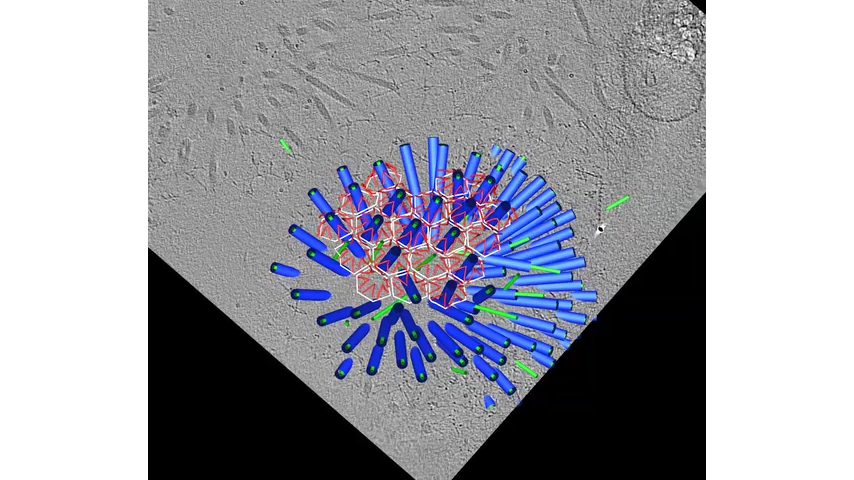

When the T6SS fires, the helical outer sheath twists into a shorter, wider form, a conformational change that provides the energy to explosively propel the inner dart, cargo-first, out and into its target (⇩). In some species, like this Vibrio cholerae, the outer sheath will then be recycled, broken down into building blocks that can be used to rapidly assemble a new machine. Other species build again from scratch, translating new protein building blocks. Warfare is dynamic, with cells rapidly assembling and firing T6SSs. Cells have even been observed to engage in T6SS duels, with an attacked cell building and firing a T6SS back in the direction from which it was hit. (You can see fluorescence microscopy of these duels on YouTube.) Some species assemble batteries of parallel T6SSs (⇩).

These contractile weapons evolved from the same ancestor as the “tail” structure viruses called phage use to inject their genetic material into bacteria and archaea (more on that in the next chapter). Some related bacterial weapons are even closer to the phage tail, in that they are released to the environment in a primed state, waiting to bump into a target cell to fire. The target is recognized by filamentous proteins called “tail fibers,” the same identification mechanism used by phage. Other members of this evolutionary family are even stranger, like the Morphogenesis-Associated Contractile structures (MACs) released by a marine bacterium (⇩).