Being able to selectively move things into your cell enables it to do some powerful things. It also poses a structural problem. Remember that water can pass freely through the membrane, which means that increasing the solute concentration inside relative to the environment outside will cause water to rush in as well, introducing a pressure (known as turgor pressure) on the membrane. Lipid bilayers, unfortunately, are unable to withstand much pressure. If your cell lives exclusively in a constant, and fairly high-osmolarity, environment (like our bodies, in the case of the pathogenic Mycoplasma genitalium you just saw), it can balance internal and external osmolarity to minimize turgor pressure on its membrane. But most cells experience more variable, and dilute, environments. How could you keep your cell from bursting in such conditions?

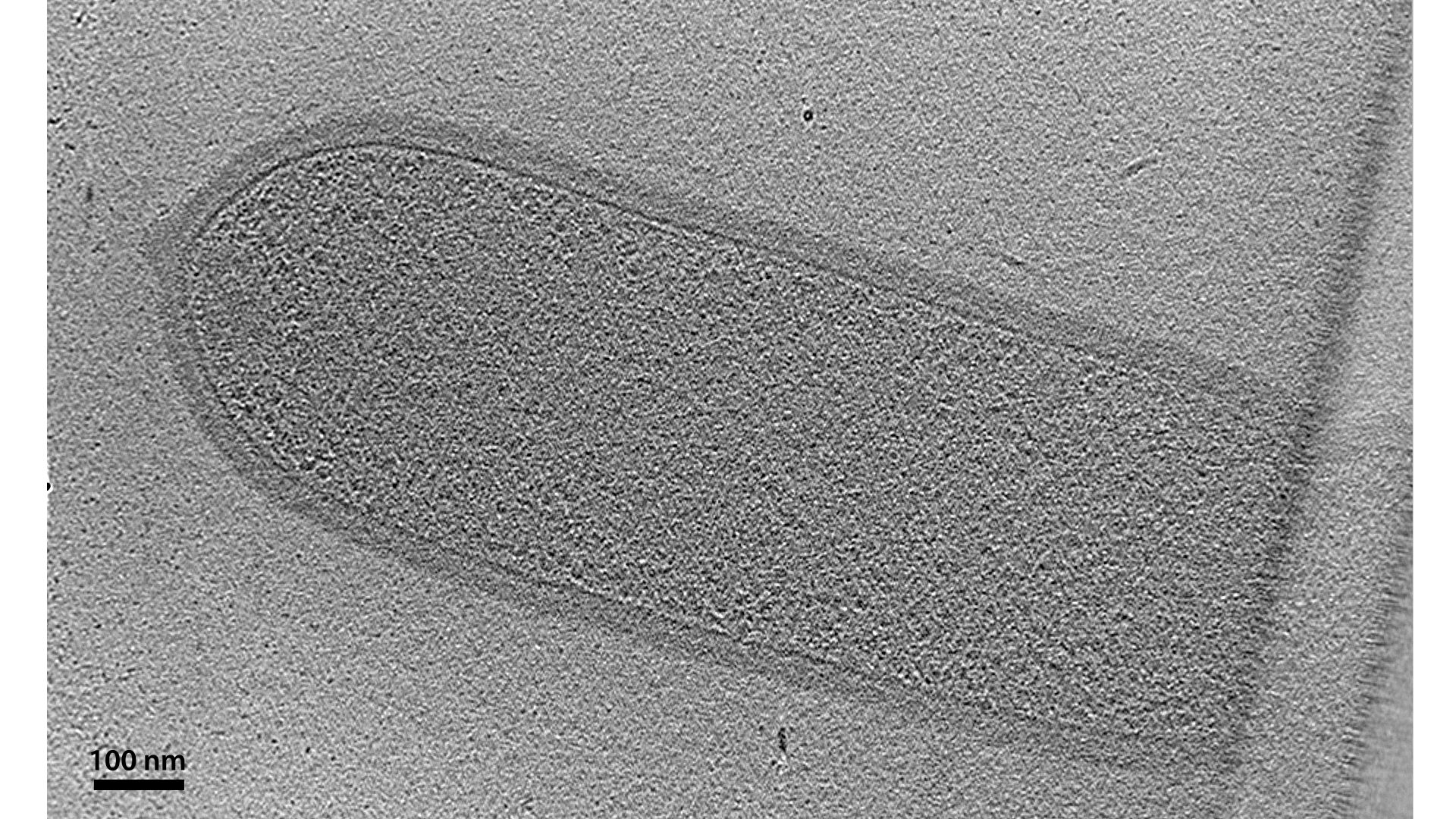

You might want to add some rigid scaffolding outside the membrane to buttress it against turgor pressure. Nearly all bacteria do this with a material called peptidoglycan: long stiff polymers of glycan sugars crosslinked by short peptides into a chain-mail-like mesh. The full scaffold of this material surrounding the cell is called its cell wall. In monoderm bacteria like this Listeria monocytogenes, the cell wall is significantly thicker than the membrane. It comprises several layers of peptidoglycan, which are indistinguishable at this resolution, so the cell wall appears as a uniformly textured layer (⇩). It remains a mystery how large molecules can pass through this dense layer on their way to and from the cell.

Some archaea also have cell walls, made of a molecule similar to peptidoglycan (⇩). Most archaea, though, rely on a different structure for support, which you will see in a few pages.

A wall can be a boon to your cell, but it can also prove a liability in certain conditions. For instance, many antibiotics target the cell wall. Some bacteria have developed the ability to jettison their walls in such conditions, taking on an amorphous, so-called “L-form” (named for the Lister Institute where it was discovered).