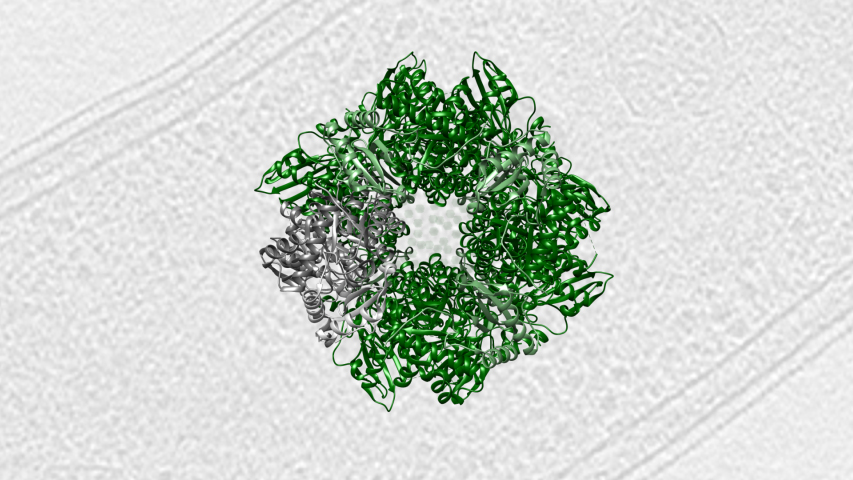

One of the most impressive bacterial microcompartments is the carboxysome, which some species use for carbon fixation (the conversion of carbon dioxide into usable fuel molecules). Carboxysomes contain tightly packed copies of an enzyme called ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, or more succinctly, RuBisCO (⇩), which is the most abundant enzyme on Earth. In this case, the shell does more than simply concentrate the enzymes. Oxygen competes with carbon dioxide for binding RuBisCO, so the bacteria include another enzyme in the compartment which converts bicarbonate (HCO3) into CO2, increasing the local concentration and making it readily available to the RuBisCO. The shell is permeable to HCO3 but slows down the diffusion of CO2 out, and O2 in. Carboxysomes were probably unnecessary in early cells because the oxygen level of the environment was much lower. Cells, like this Thiomonas intermedia, can contain many carboxysomes. While most are icosahedral, there is significant variation in their forms (⇩).

In this case, the microcompartment protects its contents from the rest of the cell, but they can also do the reverse. Some metabolic pathways generate toxic intermediates, and bacteria have evolved microcompartments that sequester them so that they do not interfere with other processes in the cell.